SAN FRANCISCO

by Yoshi Yubai

Privilege confers blinders. But privilege involves a kind of enormously complex mosaic of perception akin to what Cronenberg showed us in The Fly, his marvelous evocation of how a tiny commonplace Diptera housefly perceives “reality.” Privilege itself is an almost infinite hegemony of signs and signifiers relating not just to materiality (clothing, shoes, hairstyle, personal luggage, automobiles, architecture, city planning) but to behaviorality, (having to do with everything that constitutes body language — from posture, positioning, walking, gesturality, eye contact, facial expressiveness, body expressiveness, accent, timing, and much more).

Privilege involves race, nationality (not necessarily the same), gender (now a spectrum), age, family (or lack thereof), income levels, education, “looks” (as in “good”), intellectual-cultural-experience, travel-experience, and that bête noire of American democracy, “social class” (which most people pretend doesn’t exist).

On April 8, 2002, a 21-year-old Japanese male RE/Search fan travelled from Hiroshima, Japan, to San Francisco expressly to meet RE/Search. His name was Yoshi Yubai and already he perceived that something he resonated with — a search for “incredibly strange” — could be enhanced, developed, and extended by a personal meeting (and subsequent connection) with the RE/Search office. He stayed 200 feet away at the Royal Pacific Motor Inn where William S. Burroughs had once stayed in 1981. He brought with him his Japanese cultural upbringing which involved being extremely polite, quiet and unassuming, immediately helpful-and-of-service, and relentlessly curious. But already he was his own man. He looked at most of the 10,000 books in the RE/Search library and focused on what attracted him the most: Flemish painting (Hubert van Eyck, et all) from the lowlands of Europe. Eventually he would visit many of the world’s city museums to see these paintings in person, and buy the monographs.

He also developed a friendship with photographer Ana Barrado whose extraordinary infra-red photographs are featured in RE/Search #8/9: J.G. Ballard and J.G. Ballard’s Atrocity Exhibition (the RE/Search annotated 8.5x11” edition). He had already begun studying the entire history of world photography, spotlighting obscure Japanese photographers, and he decided to shoot black-and-white film rather that more-inexpensive digital alternatives. In Japan he studied darkroom techniques and eventually became a contributor to the Japan Vice magazine website, also contributing verbal texts and interviews.

After that first visit, Yoshi stayed at the RE/Search office as an “adopted son” and this home base possibly enabled him to visit the U.S. more often and for lengthier periods of time. Long ago he stayed a year while officially enrolled in a full-time English-language study course. A perfect guest, he spent most of his non-school hours exploring the Bay Area, often returning late at night so as to give his hosts maximum privacy. (A very sensitive roommate, probably unparalleled.)

Yoshi began taking more photographs, other of color and black-and-white, as well as seeking out more and more independent artists. He was drawn to the most- “outsider” individuals existing at the boundaries of the official “art world,” such as Monte Cazazza of the Industrial Culture Handbook; Mickey McGowan, curator of Marin County’s “Unknown Museum”; John Whitehead, semi-figurative landscape painter; Charles Gatewood, self-described “family photographer of the American Underground”; and Yosuke Konishi, founder of the Nuclear War Now! noise-music record label.

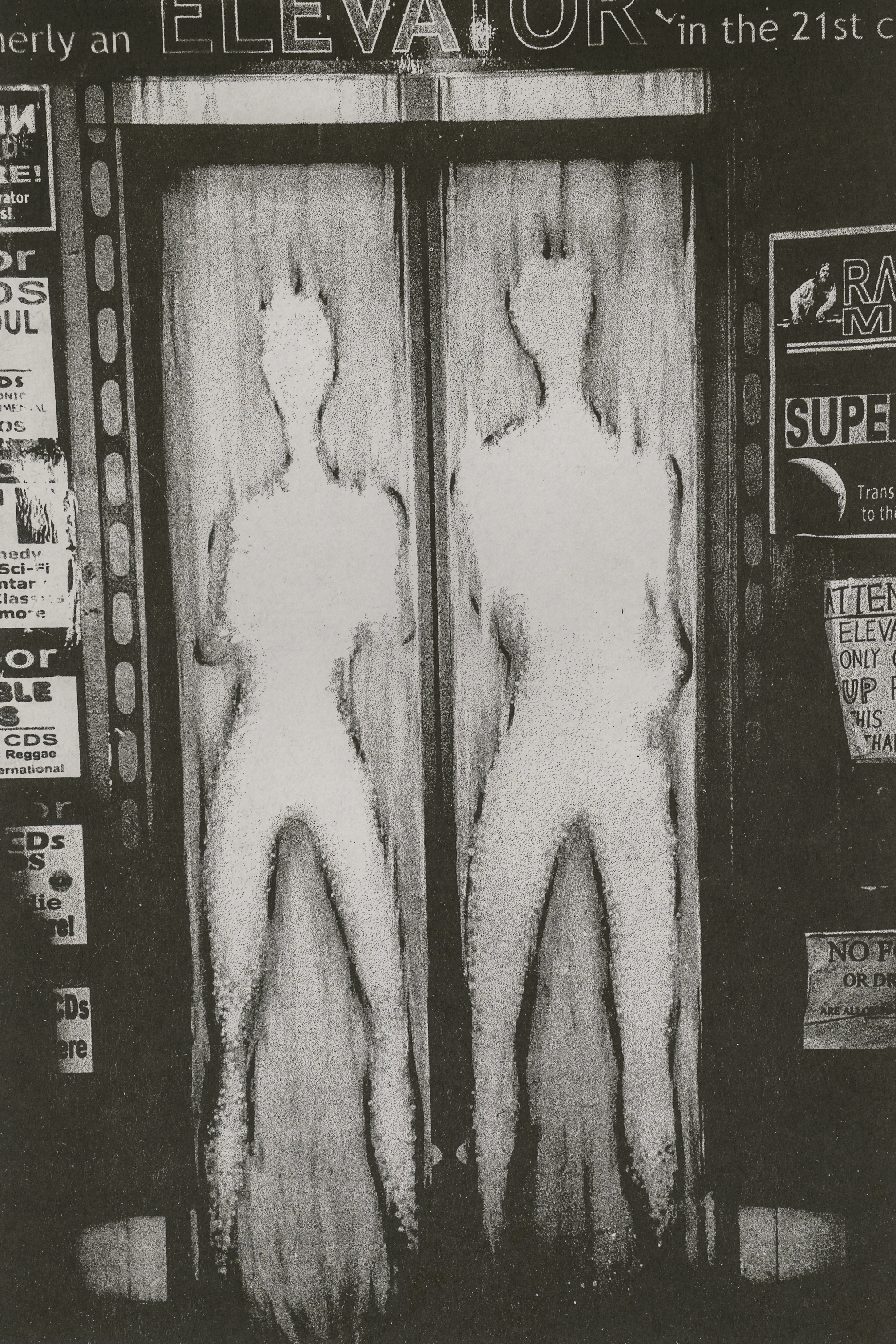

As he became more courageous staying with us through the years in San Francisco, Yoshi borrowed our cheap mountain bike (purchased for $40 from the Oakland Salvation Army) and began exploring the somewhat-dangerous Tenderloin during the post-midnight hours. More than once he had pedal furiously away from a dangerous situation. But he wasn’t just photographing the city’s homeless, mentally-ill and the non-white unemployed— he had an eye for anyone who stood out on San Francisco’s sidewalks. He knew the principle that anything in a photograph is an “actor,” and such earlier had internalized Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” “holy grail” epiphanic shutter-clicking.

At some point Yoshi succeeded in making the difficult move from his hometown of Hiroshima to the major city of Tokyo. At a Tokyo Art Book Fair a year ago he met Max Stadnik, a founder of Tiny Splendor Press, which not only publishes but prints their own independent books and zines on a Risograph machine (a “medium” of stand-alone technology which has come into its own, worldwide, in the past fifteen years). Max agreed to publish a book of Yoshi’s black-and-white photographs shot on analog film and hand-printed in a darkroom to produce silver-gelatin prints, and here we are.

Like Diane Arbus, Yoshi often seemed to be personally involved with his subjects, judging by the smiles he captured. Longtime denizens of North Beach will undoubtably recognize a sidewalk “supermodel” who is often sprawled outside The Saloon, and a hirsute sidewalk vendor who frequently displayed his wares next to the storied City Lights Bookstore. The more urban neighborhoods; Market Street, the Tenderloin, the Mission District, Colt Tower, Fishermans Wharf— can all be recognized. More importantly, key archetypes of San Francisco’s citizens who set foot on its sidewalks can be studied in their darkest shadows, captured by the non-judgmental eye of an impartial-yet-somehow-sympathetic outsider traveling through a parallel alien planet.

Yoshi’s itinerant “fly-on-the-wall” images have captured the true history of Future-San Francisco-in-the-Making, from Bohemian Paradise to Tech Heaven, unvarnished by governmental-mayoral propaganda or tourist-brochure whitewashing. The last of the pre-tech-oligarchy real humans are revealed in all their panoramic poetic splendor, before the end of the analog world as we once knew it. Yet, as Yosuke Konishi said long ago, “Only Analog Is Real.” Maybe the Digital World is already extinct; we just don’t know it yet. Only time will tell.

—V. Vale, San Francisco, January 2017

7" x 10.25"